|

|

|

Journey to the Center of India, 2006, Part 2, November 19, 2006

Still in Nagpur

(There might have been some confusion, for which we apologize. As we write this, we are, indeed, safely back at home in Kandy, Sri Lanka.)

One evening, at the Blue Moon, Bhante introduced us to one of his former classmates at Dr. Ambedkar college in Aurangabad, Mr. Mudhar Meshram. He was now working as a professor at a small teachers' college Ambajogai, Maharashtra. He, his students, and some of the other professors at the college wanted to study Pali in an intensive three-month course. He asked if we could help find a teacher in Sri Lanka. They would take care of transportation, meals, and lodging. They would also offer a small stipend. We promised to do what we could. This was just one more example of Indian Buddhists' love and respect for the Pali language.

The ceremonies in Nagpur were October first and second. The next day, we took a car to Mansar, a town about two hours away, which we had visited two years ago. One of the important attractions in the area was the excavation site of a monastery/stupa believed to be connected to the great teacher Nagarjuna.

|

|

|

More relevant to modern-day Buddhism, however, was the bhikkhu training center in the town. We had toured the half-finished building in our previous trip. This time we had come for the dedication and opening of the completed facility. The center was under the direction of Ven. Sasai. It was a beautiful building, with airy and spacious dormitory and class rooms. In the center was a large shrine room with a magnificent standing image of the Buddha. The ceremony began with the dedication of this hall and chanting to "open the eyes" of the image. The principal guest of honor at this ceremony was the man who donated the lnew building for the center. Later, he made a touching tribute to his elderly mother who also attended.

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

||||||

At the official ceremony in a tent nearby, the "keynote address" was given by a Vietnamese monk. In line with the occasion, being the opening of a bhikkhu training center, his theme was the Vinaya, the monks' discipline. He strongly disparaged wayward monks who did not follow the rules, which seemed to include most Indian monks, while praising those of his own tradition, whose discipline, he intimated, was pure. Nobody disputes the need for proper vinaya training in India, but we found his tone somewhat ironic, considering the tendency in Mahayana to alter and adjust the vinaya rules. We also remembered the many times in Japan that we heard the claim, for example, that Mahayana Buddhists were vegetarian, while we, two Theravada Buddhists, often had difficulties keeping a vegetarian diet in Japan. In fact, we never met a Japanese priest who did.

Another speech, which we later understood from Bhante's translation, compared Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism, in terms of the treatment of women, concluding, of course, by asserting that Buddha taught equality of all, regardless of caste, ethnicity, or sex. Apparently, this had weighed heavily in Buddhism's favor with Dr. Ambedkar, who was very concerned about sexism within the Dalit community. Visakha's speech, which was short and sweet, stressed her joy as a Buddhist convert at being with so many others who had themselves chosen Buddhism.

Here, as elsewhere, throughout our trip, Dr. Ambedkar's name was often preceded by the epithet "Bodhisattva." The more we learned of his selfless, untiring work for those less fortunate than himself, the more we felt that this was appropriate. In contrast to this, it was interesting to note that many Dalits who had achieved some recognition often used their influence for political or economic benefit for themselves more than for the movement as a whole. We also suspected that many Dalits returning from the UK, Australia, and Canada of being rather proud of themselves, speaking English to each other and, lording it over the "locals." Dr. Ambedkar never fell into this trap. He was serious when he intoned the French Revolutionary call for "Freedom, Equality, and Fraternity!" It was his insight that recognized these same principles in the Buddha's teaching.

After the ceremony, we went to the small vihara nearby for the conversion ceremony to which the young man in Nagpur had invited us. To one side, a dais with a canvas roof had been erected. On the grass in front of the dais, mats had been spread for several hundred people. The mats at the very front were obviously for those who would be converting. In the back were chairs for more. We sat on the dais with Bhante, Sasai-sensei, and other VIPs. Of course, we were also called on to give short speeches. The ceremony began before dusk. We could still see what was going on when we all took Five Precepts and the new converts accepted the twenty-two special precepts. It became gradually darker until no one could see anything. The speeches never stopped--not even a pause. After a half-hour, someone finally brought a few fluorescent flashlights (torches in this part of the world) and placed them strategically around the dais. Suddenly a new group, including some Tamils from South India, arrived and mounted the stage to pay respect to the monks. In Nagpur, we had purchased about twenty-five pictures of Buddha which we asked the MC (the young man who had invited us) to distribute to the new converts. We had wanted to buy more, and should have, for there were about thirty converting, but that was all the vendor had, and, as it turned out, there were enough for each family to get one. It was a pleasure to be able to give something since we'd been so often on the receiving end.

That night, the country road back to Nagpur was even more hair-raising than usual. In addition to cars, buses, lorries, tuk-tuks, trishaws. bicycles, pedestrians, buffaloes, cows, and goats, there seemed to be an inordinate number of lorries crawling along without taillights, not to mention the unmarked ones parked partially off the road, completely invisible, and just waiting to be hit. One huge lorry had only a tiny bike reflector in the middle of its black back bumper. The road itself was a maze of potholes and narrow bridges. Every day we were horrified by newspaper reports of accidents. That morning we had read about a nasty hit-and-run on a flyover in Nagpur. A young engineer on a motorcycle was hit by a Maruti and sent flying over the railing to his death below. Minutes later, the same speeding car hit another motorcyclist who was in the hospital in critical condition. The photos were chilling.

The same newspaper had another little news story about a Dalit man set afire by the landowner he worked for after he had asked for a day off for the Durga holiday. His mother had tried to come to his defense as he was being beaten, but she was also knocked down and thrashed. The poor man was in the hospital in critical condition, with burns over 85% of his body . The article added that the landowner was a repeat offender.

For a report of yet another recent atrocity committed against Dalits, which actually caught the attention of the world's Buddhists: <http://www.buddhistchannel.tv/index.php?id=70,3324,0,0,1,0>

For several years we had heard of the Dalit Buddhist community in Detroit, and Ven. Dhammananda, the Bangladeshi monk in Detroit, had tried to arrange a meeting for us to meet them and Yogesh Varhade, an activist living in Canada. We had spoken with Yogesh on the phone once from Mumbai, but had never managed to meet him. Actually, Yogesh himself called our cell phone just after we left Flint and suggested we meet the weekend we were in Virginia. Well, this world being small, we finally met him in Nagpur. The Ambedkar Centre for Justice and Peace, of which he is president, organized a seminar in Nagpur on October 4. The scheduling was perfect, and we agreed to participate.

|

|

||||

|

For more information about the activities of the Ambedkar Centre for Justice and Peace:

<http://www.web.net/~acjp/index1.htm> <http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-8053721464287659805> |

|||||

As anticipated, the proceedings started fashionably late, which meant that immediately after opening remarks, everyone had to take a "tea break," while the monks (and we) had lunch. Thus, the first panel discussion, "The Buddha and Ambedkar," that we were to take part in, did not begin until after noon. The first speaker was a Brahmin academic professor of Sanskrit, who had converted to Buddhism in 1993. Her speech, which jumped back and forth from English to Hindi (or Marathi--we were never sure which was which) was mostly about the position of women and Dalit women's organizations.

The presentation by an Indian monk, Ven. Vimalakirti Gunasiri, was extremely interesting. He described some of the popular misunderstandings of Dr. Ambedkar's views on the Buddha's teaching and expressed the belief that what the leader had espoused was actually in accordance with Theravada doctrine. In a short speech, Ken spoke of the need for proper bhikkhu training in India. He pointed out that, although everyone was well aware that Buddhism had entirely disappeared from India, the religion had also almost died out in both Sri Lanka and Burma. Both countries had sent missions to seek monks to help revive the ordination procedure. Of course, after that, it would have been necessary to re-establish the great teaching monastic centers. This is exactly the situation India was in now. Shouldn't we all, therefore, work to help re-establish those centers, such as Nalanda, in India, so that Buddhism could one again flourish in that country?

|

|

We were eager to learn more about Ven. Vimalakirti Gunasiri, for, in the program, he was listed as the Dean of Mahanaga Sakyamuni Buddhist Seminary in Nagpur. As soon as the panel discussion finished, we approached him and introduced ourselves. He was delighted to meet us and showed us his address book where he had written the Buddhist Relief Mission address in Michigan which he had intended to write for assistance. Some years earlier, it seemed, he had been involved with the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order, established by Sangharakshita, but had been disappointed, left them, and gone to Thailand, where he ordained and studied. He had been invited to teach at Mahachula University, but had refused, insisting that he needed to return to India. Back in Nagpur he had started his school just this year, beginning classes in June. The school, we learned, was not exactly a bhikkhu training center, but a Buddhist School, offering a B.A. in Buddhism to both men and women. Tuition fee was waived, however, for any young men who ordained, and the school provided serious training in Pali and the vinaya, the two subjects essential to a proper training center.

Ven. Gunasiri invited us to visit his school. Unfortunately, he was leaving for Pune that night, so the only time would be immediately. Since the seminar was taking a break for lunch, we decided to leave. We explained the situation to the organizers, made our apologies, and headed for the school, which was in a vihara we had passed on the way to Mansar. The vihara seemed to be under construction, and Bhante explained that the founder of the temple, Ven. Bhadant Anand Kausalyayan, had had lofty plans, but had died before accomplishing them (anicca!). The young monk who took over found that the temple grounds were quite suitable for weddings ceremonies. Consequently, weddings seemed to be the prime source of income. The temple provided the draperies and decorations, and a monk attended to bless the new couple. Hindu weddings, such as the one we went to in Andhra Pradesh, are always elaborate, expensive affairs, but Buddhists have generally dispensed with much of that extravagance, including the dowry, which can easily bankrupt a family.

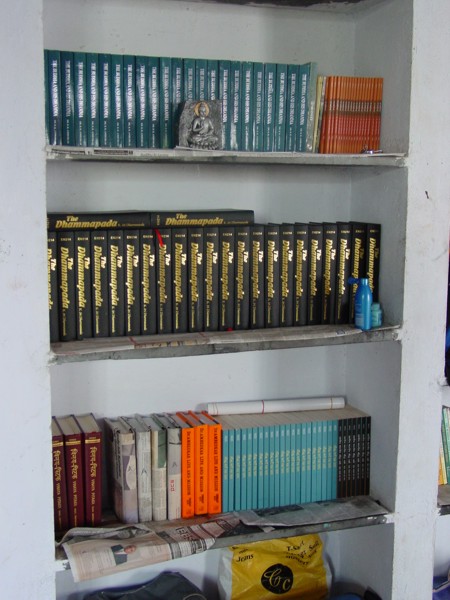

When we arrived, there was a wedding ceremony in progress, so we went quickly upstairs to the school itself. Unfortunately, this was a temporary campus. Though Ven. Gunasiri had started his school there, the rent was more than he could afford, and he needed to find a cheaper location. (While we were writing this, we received a call from him, informing us that he had found a new site, and that classes were going well.) Classes had been suspended for a few days due to the celebrations at Deekshabhumi, but the male students, all in robes, gathered in the classroom to meet with us. They had been novices for three months and behaved very properly. The medium of instruction was English, and most of them were quite comfortable talking with us, although Ven. Gunasiri had explained that one or two of the students had joined the school without speaking English at all. They were particularly keen about Pali and the vinaya, but the curriculum included geography, history, social studies, public health, and community development. Their teachers were post-graduate students from Nagpur and Aurangabad. We promised to try to enhance their library with a donation of books from BPS. We were very impressed with the deportment of these young novices. Though this was not really a "bhikkhu training center," it was doing a very good job of training novices. We hoped that some of them would stay in robes after they finished their studies and would help to build a stronger Indian Sangha.

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

Above: Library Main Hall of the Vihara Left: Click each image for a larger view. |

|||||||

Rather than return to the Seminar, which was drawing to a close anyway, we made another stop at the women's hostel. These young ladies also appeared very keen about their studies. Sitting modestly around the main hall of their quarters, they expressed their appreciation for the education and training they were getting in this unique school.

The next morning, we set out after breakfast for the "Chandramani Memorial." We expected that this was a monument erected to honor the great Arakanese monk who had established the monastery in Kushinagar and who had become the teacher of Dr. Ambedkar, administering the Five Precepts at the ceremony in 1956. The road passed by the Regimental Headquarters of the Brigade of the Guard, with its various messes, officers quarters, parade grounds, and museum. The complex was neat, tidy, and very attractive. Many Dalits had found a good place for themselves in the Indian Army when civilian society was closed to them, and that tradition continued today. At 1.2 million, India has the world's second largest army. (Guess who is #1!)* There is always a feeling that war with Pakistan is waiting to happen.

|

|

Once we got out of Nagpur, we found ourselves in the countryside. We stopped at what looked like a farm--not a monument in sight, but beside the gate, attached to the fence was a weathered sign: "Ven. U Chandramani Foundation Trust." This was actually a small Burmese vihara. The land had been donated by the father of Anil Khobragade, one of the singers we had seen performing at the Deekshabhumi. He continued living there, keeping up the grounds and caring for the resident Burmese monk. He welcomed us, and we sat with him until the monk joined us. Ven. Rakkhita Dhamma was quite young and enthusiastic. A student of Chan Mye Sayadaw, one of Mahasi Sayadaw's disciples, he had plans to develop a meditation center. He showed us the building he had already started constructing. The location, however, was quite isolated, and he admitted that he missed having good monk companions. We had a very interesting discussion of Dr. Ambedkar's book, The Buddha and His Dhamma. We were sorry we had to leave so soon, but lunch was waiting for us back in Nagpur.

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|||

Travel in Maharashtra always took longer than anticipated, so Bhante called the family to tell them that we were on the way, but that we would be a little late. Lunch was being offered in the home of a very devout family that Bhante had known for many years. Both Mr. Chandrakapure and his wife, Shulini, were Ayurvedic doctors, and they insisted that Bhante visit them whenever he was in Nagpur. One room of their house was always open for a monk to stay. Sadly, both parents carried the sickle cell anemia gene, so their children suffered from that disease to varying degrees. One son was particularly affected and in considerable pain. We were very surprised to learn that it was Mr. Chandrakapure's brother, Ven.Sumanavanno, who had reprinted and popularized the "Magic-eye Buddha" that we discovered on our previous trip two years ago. After a delicious lunch, which included jeera (fennel) rice and marvelously rich milk rice with raisins and cashews, we joined the puja in their shrine room. They invited to stay with them whenever we were in India, and we returned the invitation, urging them to visit Sri Lanka.

When we got back to the hotel, we found that the electricity was off. A generator was running, and that provided enough power for the lights, but not for the elevator, so we climbed to the second floor, which really was the fourth. (Since there were no guest rooms on the floor above the ground floor, they didn't even count it.) As in many old elevators in India, the doors were folding grates; the inner one had to make contact before the elevator would move. Strangely, whenever the elevator stopped, it was always off by several inches--sometimes higher, sometimes lower, than the floor, but never the same.

Taking advantage of, at last, having a break in our busy schedule, we hied ourselves to an internet cafe (Cyber Cafe, in India--without coffee, of course). While Bhante checked his various addresses, we opened our mailbox and found 414 new messages, of which more than 300 were junk! Thank goodness that Earthlink provides a "Known Spam" filter, so we didn't have to deal with the 2681 messages in that mailbox. We both worked as fast as we could on sticky keyboards, to reply to the personal messages. Nagpur has dreams of becoming a hub for India and an international city, but it does not yet have even one four-star hotel, so no possibility of a wireless connection, such as we enjoyed in Mumbai.

The morning of our last day in Nagpur, we were picked up by Amit, a young man who had greeted us at the hotel our first night there. A manager in the Nagpur office of Coca-Cola, he was one of the leaders of young Buddhist activists in the city and had repeatedly expressed to Bhante his desire to become a bhikkhu, but he was not yet ready to commit himself to such a big step. We assured him that when he did, we would support him. There were three young Japanese staying with him; they were working with Sasai-Sensei on a biomass electrical power project in Mansar. When Amit's parents came in, they greeted us by touching our feet. Although this happened quite often, we always felt that that kind of reception should be reserved for monks.

Lunch was being offered by another family of activists, the Jagtaps, who lived nearby. The host's brother showed us an album of photographs documenting the projects of their Buddhist organization, which often set up free eye clinics and regularly visited the local mental hospital. Many friends and relatives joined the puja and the Dhamma talk, which seemed more substantial than usual. Perhaps we were learning a bit of Hindi, for it seemed that we could follow the general drift. The couple had one son, who was handicapped, but obviously much loved. He was a sweet little boy with a beautiful smile, and he sat respectfully in front of Bhante during the worship, remaining quiet and respectful as long as he could. After the formal service, Bhante talked long with the young people, blessing them and tying strings on their wrists, as is customary in many Theravada countries. Whenever the word went out that there was a monk in the neighborhood, people flocked to the house from all around, and all of them wanted blessings.

That afternoon, Bhante suggested we visit a "women's group," so we hailed a tuk-tuk (called "auto-rickshaw" in India). Since we were not taking the wheelchair, we crowded into one vehicle, with Ken sitting between Bhante and Visakha, but on the narrow wooden platform behind the driver, facing backwards. When we arrived at a lovely little vihara set in the middle of a densely packed neighborhood, we could hear the melodious chanting from within. We entered the shrine room and took the seats that had been prepared for us. About fifteen women, kneeling before the altar continued their beautiful devotions. We had never heard this style of chanting before in India, though it reminded us of the metrical chanting of the Khmer women and the nuns' chanting from Amadavat (UK). The vihara was maintained by a nun (samaneris), Ven. Dhamma Rakkhita, who resided there. Actually, during the service, workmen were finishing the remodeling of her living quarters. It was Ven. Dhamma Rakkhita, we learned later, who had provided Ven. Pannasila's robes and bowl when he ordained in Nagpur in 1993. She herself became a Dasa Sila Mata, or ten-precept nun, at BuddhaGaya in 1999. When she heard about samaneras going to Sri Lanka to study, she mentioned that there might be several from her community who would be interested. We invited her to come with them, and she said she would if Bhante went, too.

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|||||||

Bhante had some business to attend to, so we took separate tuk-tuks back to the hotel. Ours took a very circuitous route, passing a garbage dump that stunk to high heaven, but it was full of goats and cows, for whom it served as both manger and stable. Nearby was a colony of scavengers. In front of their hovels were huge piles of bottles, plastic bags, and other refuse, all neatly sorted. Little children wandered around, apparently unsupervised. Illuminated only by very dim streetlights, it was an alien and unsettling scene. These were certainly people at the bottom of society.

At the Blue Moon Hotel, none of the bellboys was young enough to merit that title. One man, who had taken care of us every day of our stay had asked us for a personal message and an autograph. He said that recently there had been no foreigners at the hotel, and he was very happy to have us as guests. He had made a point of creatively arranging the bath towels on the beds each afternoon. He had personally prepared meals for us whenever we ate at the hotel. He had also made sure that the morning cooks clearly understood what we wanted for breakfast, and that the food was to contain no chillies. He said he was sorry to see us go, and we felt that our stay had indeed been as interesting for him as it was pleasant for us. We were happy that the Durga festival was over so that we could get a good night's rest before heading out. One of the receptionists had early on informed us that he, too, was Buddhist, and he asked whether we had any amulet to give him. We wrote down his name and address, and promised to send him one as soon as we returned home, but Bhante found one which he had gotten in Sri Lanka and presented it to him as we checked out the next morning.