|

Lunch with the Yawalkars

Above: Sepia to override the tint from the skylight Left: A bookmark on the kitchen wall; Extended family and friends in the living room |

||||||

Journey to the Center of India, 2006, Part 3, December 8, 2006

From Nagpur to Chikaldhara

From Nagpur we took a pleasantly uncrowded back road to Warud, a quiet town on the Madya Pradesh border. Lunch was being offered by the owner of a gas station on the main road. Their home was just behind the station. We were seated in a very large living room with an almost circular archway leading to the dining room. While we were waiting, many other guests arrived to pay their respects to Bhante, including a poet, a musician, and a "Dhammachari" (teacher), with Friends of the Western Buddhist Order. One guest that Bhante had particularly wanted us to meet was a young journalist who had studied in Minnesota and now writes for various newspapers, mostly about topics of interest to the Dalit community. She came with her parents, who had also both studied in the United States. The dining room was very large. An interesting feature was a green plastic skylight, which colored everything in the room even in the photos taken with a flash. All around the house there was a profusion of plants and trees. It seems that the owner also ran a nursery, and many of the trees for Bhante's new monastery had come from there.

|

Lunch with the Yawalkars

Above: Sepia to override the tint from the skylight Left: A bookmark on the kitchen wall; Extended family and friends in the living room |

||||||

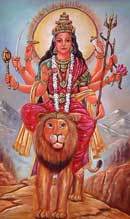

y junction we encountered a Hindu procession leading an image of Durga to be immersed (discarded) in a body of water--a canal, a stream, or a small reservoir behind a dam. These processions were incredibly noisy and raucous with drumming, dancing, and, apparently a lot of drinking. Clouds of pink powder, reminiscent of Holi, the festival we had observed in Kolkata in March, filled the air. Many of the revelers sported pink clothes, hair, and skin. After some U-turns and detours, we arrived at the Sherdurjana Ghat Buddha Vihara, where several hundred devotees sat quietly waiting for us. As we mounted the dais and took our seats, one of the noisy processions passed directly in front of the temple.

|

||||||

|

Durga

|

On the dais

|

|||||

There was no monk resident at the vihara, but the lay people had gathered daily throughout the rainy season retreat, chanting vandana, listening to the Dhamma, and discussing the teachings among themselves. They were delighted to have this opportunity to receive the five precepts and teaching from Bhante.

Of course, we were also asked to say a few words. Ken chose as his theme the opening lines of the famous Kipling poem, "If you can keep your head, when all about you, others are losing theirs," praising the small congregation for practicing so diligently amidst the chaos. Bhante was a bit surprised at first, but he translated faithfully, and everyone (we hoped) understood. We were touched by all the individual greetings, especially from the little children, who responded so sweetly to our smiles.

Malkapur was very close to Satnur, the village where Bhante grew up. He showed us the house where he grew up and where his parents still live. When he was a boy, the village was fairly evenly split between Tribals who spoke their own language, and caste Hindus. His family were the only untouchables. Now, however, the population is approximately one-third Tribal, one-third Hindu, and one-third Buddhist. Bhante told us that when he was a child, named Rajiv, his mother had taught him to worship the Hindu gods, but he had not understood why he wasn't allowed to go to the temple. He had been quite unaware of untouchability until he helped a man deliver a cow to a Shudra's house and got scolded for it. He wondered why he was being blamed for being helpful.

| A neem tree; a house in Satnur; jawar (millet), a staple in Maharashtra (also eaten in Sri Lanka, where it is called kurakkan) | ||||

One day, when he was in the seventh standard, he wore a new shirt and pair of pants to school. The teacher mocked him, saying that the boy was acting uppity, like a Home Minister. At that time, Jagjivan Ram, a Dalit from the shoe-maker caste in Bihar was a minister in the Indian Government. A shameful incident took place in 1979. When Ram unveiled a statue of the great scholar and freedom fighter, Dr. Sampurnanand, at the Sanskrit University in Varanasi, local brahmins, outraged that Ram had dared to "pollute" the statue with his touch, immediately brought water from the Ganges River to give the image a ritual bath to "purify" it. Despite such prejudice against him for his "low birth," Ram served uninterruptedly in the Indian Parliament from 1936 to 1986 (a record) and held many ministerial posts, including Deputy Prime Minister.

Because of his untouchability, Rajiv was often scolded and even beaten by the teachers, some of whom were low-caste sudras, themselves severely discriminated against by upper caste Hindus. Whenever he got into trouble, his parents scolded him, reminding him that they were very poor and the only leather workers in the village. "Remember," they admonished him, "if you live in the water, you don't make an enemy of the crocodile!" Rajiv was also beaten by school bullies, but his solution was to study martial arts so that he could defend himself. That training was also his first link to Buddhism, although he didn't realize it at the time. He devised tricks to get back at those who looked down on him. One year, just before a festival in which an idol of Ganesha (the elephant-headed god) was going to be taken in a procession, a Shudra girl accused him of spoiling "our Ganesh" by touching the statue, and he was severely scolded by the temple priest. Since he was a school monitor, he left a window unlatched, and, that night, he returned unseen to the hall where the idol was kept. He cast a string with a hook through the window, caught it on the elephant's trunk, and with a jerk broke it off. When the damage was discovered, the high caste students were horrified, but they had no idea who had done it. Rajiv even helped the girls repair the image with twine, but it was a deformed Ganesha they carried in the procession.

|

||

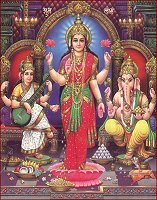

| Ganesha | ||

When he was sixteen, Rajiv's parents began seriously thinking about his marriage. Several relatives visited with proposals for suitable girls. That summer, he went to the Sherdurjana Ghat Library every evening to read and to borrow books, thus beginning his social education. After reading Dr. Ambedkar's life story, he rejected his parents' plans for his future.

His mother shopped in the weekly market in Malkapur, and, one day, she happened to meet Balkrishna Bagde, a Buddhist social worker and activist, who suggested that Rajiv continue his studies at Milind College, established by Dr. Ambedkar, in Aurangabad, where his son was studying. Mr. Bagde thought that Rajiv's marks were perhaps high enough for financial assistance. His mother was so delighted at the idea that she bought her son new clothes and a traveling case. She also bought a ticket for Mr. Bagde, so that he could accompany Rajiv to Aurangabad.

Rajiv enrolled in Milind Collage of Science, but was initially overwhelmed because all the science and math courses were in English. The new environment was daunting. He'd never been in a big city before and experienced homesickness. After a month he returned home with stomach pains and nasal congestion, as well as other ailments. He quickly recovered, but, as he looked around at his village, he realized what his future would be if he did not finish his studies. He returned to Aurangabad and resolved to succeed.

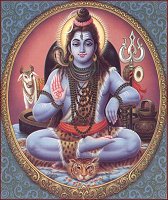

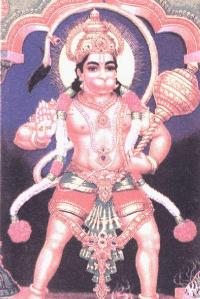

At Milind College, he continued worshiping his statue of Hanuman (the monkey god). In his room, he also had pictures of Laxmi (goddess of wealth), Saraswati (goddess of knowledge), Ganesha (god of wisdom), and Shiva. His roommates, who were Buddhist, argued with him about his daily worship, but he wasn't ready to abandon those gods. His roommates also cooked fish and meat, which upset him a lot since his family had been vegetarians for three generations. Twice, he was kicked out of his hostel for quarreling over religion. Fortunately, the Principal, Mr. Shinde, visited his room and was able to arrange a compromise, and Rajiv was able to successfully complete his third term.

|

|

|

|||

|

Shiva

|

|||||

|

Laxmi , Saraswati, Ganesha

|

Hanuman

|

||||

It was about that time that he heard about the Long March, part of the campaign demanding that the government honor the decision made some years earlier to change the name of Marathawada University to Dr.Babasaheb Ambedkar University, Aurangabad. This decision had been opposed and postponed by strong Hindu organizations. This was Rajiv's first time to participate in any protest. Friends had told him that it was easy for students to pass from the eleventh standard to the twelfth, so, in his eagerness to join the march, he skipped his last exam.

On the morning of the big day, the marchers gathered in front of the University Gate. After taking refuge in the Triple Gem and undertaking the Five Precepts, they began their 1643-kilometer march to Delhi. His group was under the leadership of Mr. Manohare, a member of the Maharastra Transportation Corporation. Rajiv wore a blue cap and carried a long bamboo pole with the square blue standard of the Republican Party of India, which had been founded by Dr. Ambedkar.

|

|

|||

|

The University Gate and a statue of Dr. Ambedkar in Aurangabad

|

||||

It took sixty-four days to walk to Delhi, where, on April 14, 1986, Rajiv joined in a massive celebration of Dr. Ambedkar's birthday in front of the Indian Parliament. This was also his first visit to the capital city, and he tried out many new things, like elevators. The importance of the march for Rajiv was the opportunity to discuss the Dalit movement with his fellow activist. He learned a great deal, and it was a heady experience, one of the turning points in his life.

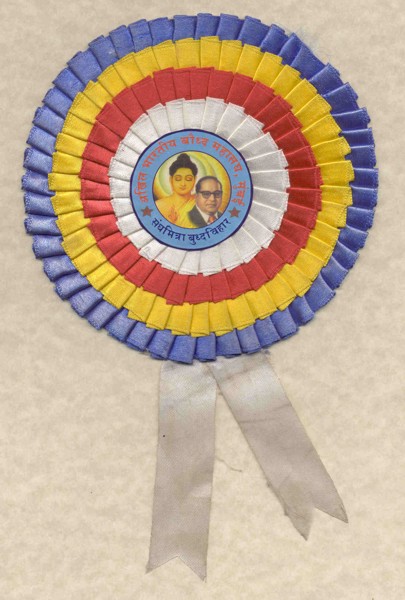

In Delhi, he got separated from the leader, who had his luggage. He spent two days, virtually lost in the capital, without money, looking for another group. All he had were some posters friends had given him. Finally, he went back to the station. Searching the trains, he finally boarded the Jammu Tawi-Madras G. T. Express.. Many hours later, he noticed that the temperature was dropping and wondered why he was freezing. Inquiries revealed that he was indeed traveling north. He disembarked at the next stop and caught a train in the proper direction. Surprisingly, all his travel was free. His "pass" was the Dr. Ambedkar badge on his chest. (Even to this day, many impoverished Dalits travel to conversion ceremonies in Buddha Gaya without paying. Their rationale is "We've been cheated all these years!")

|

||

| A Dr. Ambedkar badge, perhaps similar to the one Rajiv was wearing. | ||

He stopped in Itarsi to visit his grandfather's house and to get a few rupees, and then continued home. At his parents' house, he replaced the pictures of the Hindu gods with his posters of the Buddha and Dr. Ambedkar. When he arrived back in Aurangabad, he discovered that his roommates had torn up his pictures of the Hindu gods, but he wasn't the least bit upset about it. In fact, he himself destroyed his old statue of Hanuman. Even though he had been gone for two months, he received passing marks for all classes and immediately decided to change faculties to Dr. Ambedkar College of Arts and Commerce. With the help of a Professor at the college, Mr. Dongre, whose family we met when we first visited Aurangabad, he easily found a hostel.

|

|||

| Dr. Ambedkar College of Arts and Commerce | |||

During Divali Festival vacation, Rajiv returned to Satnur and started a Buddhist youth group.

He also organized a women's group which collected two rupees from each member each month to put up a statue of Dr. Ambedkar for the Dalit colony. Every evening during the rainy season, people gathered faithfully for two hours to listen to a reading of Dr. Ambedkar's book "Buddha and His Dhamma." At the conclusion of the rainy season, on the full moon of October, the statue was inaugurated. Sasai-sensei came for the ceremony. Rajiv welcomed him and washed his feet. Rajiv was pleased that his mother recited the Three Refuges and Five Precepts along with him.

The campaign demanding the renaming of Marathawada University lasted for ten years. Many people were beaten in the demonstrations, and some were even killed on the order of state authorities. Once he joined the Dalit activist movement, Rajiv threw himself into it, getting arrested seven times, spending time in jail on three of those occasions. During his university studies, he had many good teachers, including Prof. Sushila Mool, who taught him Pali and Buddhism. She herself had spent a week in jail with other Dalit women. Every aspect of the Dalit liberation movement incurred great persecution and oppression from caste Hindus. In fact, that oppression has not yet changed. What has changed is the understanding which people have of themselves, their self-respect, and their faith in the Buddha.

The road to Bhante's new temple, about which we had heard so much in his email messages, reminded us (a little) of the Burmese border. Two rivers merged at the edge of the village. There was a bridge just below where they came together, but it was not yet finished. To get to the temple we had to drive through the water twice. Though it was only about a foot deep, the driver went as fast as he could, hoping the van would not stall mid-stream. (Returning, he took a chance on making it up the steep slope beside the bridge so that we only had to drive through the water once.)

The monastery sat on a hilltop overlooking a reservoir. The road went only halfway up. There was a steep, well-worn path going up, but Visakha was touched to see a brand-new staircase leading straight to the top. Nobody said so, but she felt sure that it had been built especially for her. As we ascended, we were showered with fragrant flower petals from devotees lined up on both sides. It was a lovely welcome. We were escorted into a pavilion with the familiar drapery canopy adorned with lotus designs covering the ceiling. The band continued playing as the devotees came in and sat on the mats spread on the ground. We took our seats at the front with Bhante. Dignified-looking men, all dressed in white, were sitting along the side wall, obviously a "Board of trustees." The children opened the festivities with a sweet devotional song. After a few minutes, Bhante led us into the vihara, which was entirely draped with gold, to light candles and incense before the Burmese images of the Buddha and the photograph of Dr. Ambedkar. Bhante chanted a few verses of blessing in Pali, and we returned to the reception hall, where all the devotees took the five precepts.

Then the official program began with garlands of flowers. So many people wanted to greet us and pay their respects that we seemed to receive the most, but many others were also honored, including Bhante's mother and father, whom we were meeting for the first time. The Master of Ceremonies was Bhante's brother, Dr. Ashok, ably assisted by his bright eight-year old son, Bodhiratana, who also spoke quite good English.

After welcoming and congratulatory speeches by all the dignitaries and a well-received Dhamma talk by Bhante, we moved to the edge of the hill for the foundation-laying ceremony for the pagoda. All of the existing buildings were temporary, but Bhante had designed the complex to include also a proper vihara, a library, a teaching hall, and a meditation center. When he first acquired the site, it was a barren hill, but he had planted thousands of trees, including teak, neem, acacia, rubber, and various kinds of fruit. He had also planted groves of bamboo and a multitude of flowering shrubs. The responsibility for watering all of these trees and plants while Bhante was away was given to a tribal boy who came into the village to get his education. Bhante provided him food, lodging, and support for his school fees. In return he took care of and guarded the monastery. Bhante praised him fully for his diligence and seriousness.

While the bamboo and thatch buildings were temporary, a very substantial structure was a concrete water tank. The funding for this had been donated by a Vietnamese nun from France who had traveled last year with Ven. Pannasila and other Indian Buddhists to educate herself about Dalit issues. Bhante spoke approvingly of her perceptivity and frankness: she had scolded some laymen for acting like "Brahmins," taking advantage of the monks and using the movement for their own political advantage.

The only "permanent" building on the grounds was a W.C. built halfway down the back side of the hill. Visakha was given the honor of cutting the ribbon for this impressive facility which had two water-seal toilets--one a western stool, the other one squat.

The installation of something like this was both important and revolutionary. The "dry" toilet has long been the symbol of the dreadful exploitation and maltreatment of India's untouchables. The shame of manual scavenging cannot easily be imagined. What kind of religion forces people, mainly women, to clean feces by hand and carry it away in a basket on the head? After doing this degrading work, scavengers were paid only a pittance, exposed to a myriad of diseases, and treated as social pariahs as well. The construction of dry toilets was officially banned in 1993, and many government reports have claimed that manual "scavenging" was abolished and that all scavengers had been "rehabilitated" at a cost of millions of rupees. How ironic and all the more obnoxious that the toilets were still being built and the scavengers were still employed by the same government authorities which denied their very existence. For more information on this horrendous practice, visit:

Bhante's mother kindly helped Visakha up and down the slopes as she toured the hillside. It was indeed a great accomplishment for Bhante to have been able to establish this monastery so near his home village. At first, neither his parents nor his brother had understood why he had wanted to become Buddhist. They had thought him mad to renounce the Hindu gods. They were also afraid of the Hindus in the village; they had been indoctrinated to believe that standing out was dangerous. Gradually, with patience and loving-kindness, he was able to help them to understand what he had seen and to show them that they, too, could stand up for their rights. The entire family had converted to Buddhism, and many in the village were gathered at the monastery to greet him and to pay their respects. The celebrations were concluded with snacks, tea, and devotional songs. As we left, we passed many of the villagers walking home. They smiled and waved as we exchanged encouraging calls of "Jaya Bhim!"

It was quite a long drive to Maharashtra's only hill station, Chikaldhara, which is more than 3560 feet above sea level. The sun had set by the time we started climbing, so we stopped at the last town for tea and samosas for the driver and a toilet for us. The tea shop had no facilities for visitors, but the owner directed us some steep stairs, and we used our flashlights to get to the dark toilet for the men's hostel, where casual workers paid 50 rupees for a cot. Bhante talked with some of the men who were getting ready to sleep there. The charges seemed very high to us, considering that laborers usually got only 70 or 80 rupees for a day's work. We hoped they got breakfast, too. After another couple of hours of driving, we reached the resort town. Of course, we had no idea what the landscape was like until the next morning, when we discovered we were surrounded by deep mist filled valleys. There was even a tiger preserve, with deep jungle, about twenty-five miles away.

At last, we found a use for the cheese and crackers we'd been carrying in a tin all the way from Sri Lanka--a tasty breakfast for Bhante, the driver, and us that first chilly morning in Chikaldhara.

According to legend, the Pandavas of the Mahabharata were exiled here. They say that one of the steepest valleys was formed when the powerful Bhima threw the body of their evil enemy Keechaka through the air, the force of the fall creating the huge depression. Of course, there's no story to explain all the other beautiful valleys, but that's how legends are.

Allow us here to quote a passage describing India from a book we recently acquired, "A History of India," by John Keay. ( Harper Perennial, HarperCollinsPublishers, London and New Delhi, 2002, pp. xxi-xxii)

"Boarding at random an overnight train, and awaking twelve hours later to a cup of sweet brown tea and a dawn of dun-grey fields, the traveller--even the Indian traveller--may have difficulty in immediately identifying his whereabouts. India's countryside is surprisingly uniform. It is also mostly flat. A distant hill serves only to emphasise its flatness. Distinctive features are lacking; the same mauve-flowered convolvus straggles shamelessly on trackside wasteland and the same sleek drongos--long-tailed blackbirds--festoon the telegraph wires like a musical annotation. It could be Bihar or it could be Karnataka, equally it could be Bengal or Gujarat. Major continental gradation, like west Africa's strata of Sahara, sahel, and forest or the North American progression from plains to deserts to mountain divide, do not apply. The subcontinent looks all of a muchness."

Chikaldhara, with its wooded hillsides, cool temperatures, pleasant breezes, rocky cliffs, abundant water falls, and dramatic scenery made a delightful change from the hot, dry, dusty plains below and all around. Of course, the population (more than one billion!) is one factor in this sameness bordering on monotony: the burgeoning population has destroyed the jungles and denuded the hills. In search of firewood, people have pruned and mutilated every tree. Cattle, buffaloes, and goats have eaten almost every blade in some areas. Chikaldhara was refreshing, not only for the scenery, but also for the lack of people. This being off-season, there were almost no tourists in the small town. It was the quietist forty-eight hours we had ever experienced in India. We didn't see any tigers, but our vehicle surprised some foxes, who watched us with bemused expressions before ambling off into the forest.

Bhante had his eye on several tracts of land in Chikaldhara for a meditation center. The peacefulness and the comfortable climate would make meditating there during the hot season very attractive. There was a small Buddhist community living there as well. Bhante directed the driver down some narrow lanes leading to a small fenced-in area, in the middle of which was a simple but attractive Buddha image, obviously handmade with devotion.

|

|

|

||||

|

||||||

| Click the images above to enlarge.- Below, the land where Bhante would like to build a meditation cernter. | ||||||

One of the first sites we visited was an ancient Buddhist cave, originally situated beside what would have been a magnificent waterfall, which was the origin of the Chandrabhaga River. Unfortunately, in order to create a dam and a mini power plant, the bottom half of the cave had been filled in with concrete, leaving only a very small enclosure, converted into a Hindu shrine, and creating a reservoir in front of the cave, a viewing platform, and a most undramatic cascade.

A more authentically historical site was the Gawilgragh Fort, a twelfth-century fortress overlooking the Chikaldhara Plateau.The imposing stone structure incorporated some of the cliffs to render the walls nearly impregnable.

In keeping with the laid-back atmosphere of the resort, we went to the market on Sunday afternoon, when most of the stalls were closed, but there were quite a few vendors sitting on plastic sheets with their goods spread about: lots of clothes and handmade jewelry. We remembered all their earrings we had bought for Visakha's mother in our travels. We found fruit for the next day's breakfast, and Ken bought another dhoti, asking the seller to show him how to tie it in the local fashion. The vendor, however, was wearing slacks, so we were not sure whether the lesson was genuine.

|

|

|

Our first day ended, appropriately, with a drive to Sunset Point. We thought it was at the edge of town, but we had to drive about thirty minutes through the nature preserve. Although entry was restricted, and unauthorized activity was prohibited, it appeared that peasants, perhaps tribals, who had been cultivating the land before it was declared a national forest, were allowed to continue. The rolling hillsides were covered with fields of delicate yellow flowers--safflower, we learned--grown, of course, for their oil. Sunset Point was a bit overrated, but we took a few photos with the distant hills as a backdrop before it got too dark. The sun obliged us by going down, but the sunset was not nearly so dramatic as we had seen it over Manila Bay or the Mekong River. Maybe it was just an "off" day

The next morning, Bhante and the driver got up early to venture out to "Sunrise Point," but Visakha and Ken decided to sleep in. The report was that the sunrise was no more impressive than the sunset had been--surprise!

We went "downtown" for breakfast at a small stall. We each had two plates of poha, delicious flattened rice, a Maharashtran specialty. While the cook stir-fried the rice, we peeled apples and picked the glistening arils out of a pomegranate..

|

|

||

|

Pomegranate

|

|||

After breakfast, we visited the Chikaldhara Natural History Museum, which is set in a remarkably well-kept garden at the entrance to the nature preserve. Fortunately, the building had many windows, so we could see the displays even though the town was experiencing a power outage at the time. With our telephone-flashlights we could even read the informative descriptions and awareness posters on endangered species, forest protection, and pollution prevention. A large glass case in the first hall contained stuffed specimens of several large animals, including a bear and a tiger. Smaller cases displayed smaller stuffed animals and various skeletons. In one room there was an interesting assortment of pieces of lumber, each labeled to indicate which tree it came from.

As we were leaving, one of the museum attendants, when he learned we were American, asked how much a laborer earns in the US. Remembering that the daily wage in India was about 80 rupees ($1.80), we were rather hesitant to admit that minimum wage was more than five dollars an hour.

The final scenic site was Echo Point, with another dramatic view. The sound of the nearby waterfall, amplified due to recent rains, dampened the reverberation and rendered the echo from even Ken's loud shout rather unclear. A diversion: we recalled reading somewhere that a duck's quack didn't echo, so, being skeptical by nature, we "asked Jeeves" and discovered that..., well, check it out for yourselves, and note that the experiment was carried out in our old stomping ground!

(To be continued)