|

|

|

||

|

||||

Pilgrimage 2007, April 25, 2007

Setting out

Serendipity works just fine in Serendib (an ancient name for Sri Lanka). Our Dhamma friend David arrived from Thailand the day before we left for Kolkata and would stay a month, doing useful work for BPS and adding to the calm good atmosphere of our house. Lily undertook to look after him as well as she looks after us.

Because our flight didn't leave until 2 AM, we really spent two days getting from Kandy to Kolkata. We took a van to Colombo and dropped text books off at Dushy's house. Even though Air Sahara kindly gave us an extra baggage allowance because we were volunteering to teach monks in India, we were still loaded to the max with all the educational materials.

Unfortunately, we could not check our luggage through to Kolkata, so we had to schlep our 100kg at both Chennai and Banglalore. In the latter, we had an eight-hour wait for our connecting flight, with all the luggage piled in a restaurant. As we traveled, Ken grew increasingly tired, feverish, and clammy. Actually, he slept most of the way, including at the restaurant, with his head on his cushion on the table.

When we finally reached Bodhisukha, Visakha took Ken's temperature, which rose to 101 degrees F and fell to 95. He felt miserable and developed a headache, the first he had ever had in his sixty years. Sunday afternoon, Ven. Nandobatha called the local doctor who drove over and examined him. The doctor ordered a test, and the technician came the next morning to draw blood. The results for malaria were negative, but we hadn't really expected malaria. Sri Lanka had many cases of dengue fever, Japanese encephalitis, and chikunguniya however, and we suspected one of them to be the culprit.

Although Ken is the dedicated shopper in the family, he didn't feel like getting out of bed, and we needed lots of stuff for the pilgrimage and for the monastery. Visakha went shopping in Barasat with Rajiv and his gang of friends. They seemed to know the best place to find every single item--a tiffin carrier, a thermos flask, mosquito repellent, extension cords, energy-efficient light bulbs, and wool blankets and shawls for all. Winter in northern India is cold.

Also, we wanted to make catumadhu. Rajiv and his friends had a great time searching for the highest quality ingredients. For the ghee, they scouted out the best dairy outlet in Barasat. Honey was from a pharmacy. They tried several shops before they found the perfect jaggery. Someone had suggested mustard oil, but one whiff dissuaded Visakha; it was much too strong. They didn't understand sesame, even though we had mentioned "tila," which we thought was Hindi. After sampling several kinds of oil straight from the presses, one of the men brought the right one, which, it seems, is "til" in Bengali. The final syllable had thrown them off, but "no problem!" Beautiful glass jars came from the shop of one of Rajiv's friends. The last item was a double boiler. This was a challenge, since none of the men nor the shopkeeper understood the concept. Visakha tried every combination of bowl, pot, and pan, sometimes even reversing the order suggested, but at last she found two stainless steel bowls which fit one in the other. Oh yes, we also needed a very long stainless steel spoon.

|

|

|

||

|

||||

Ven. Nandobatha had installed a new wireless connection at Bodhisukha, but it wasn't reliable. The supervisor came out but didn't seem to know what he was doing. We showed him the data switch we had brought from Sri Lanka, but he still seemed to be muddling. Finally, his technician brought the proper modem, connected it to our data switch, and "BINGO!" we were connected to broadband. All four of us English teachers will be connected to the world from all the rooms in our hostel throughout the intensive course from mid-March to mid-April.

Although we needed to get ready for the pilgrimage, Ken's condition showed no improvement. One evening, he announced that he thought he needed to go to the hospital. Ven. Nandobatha suggested the Apollo, the best private hospital in Kolkata and, fortunately, not too far from Barasat. Within fifteen minutes, Vens. Nandobatha and Ariyawantha, Visakha, and Ken were in a vehicle, heading straight for the emergency room. After preliminary and cursory checks, it was decided to admit him, so Visakha and the monks took care of the paperwork. When Visakha got back, she discovered that there had been no serious exam and that the emergency service seemed not at all prepared for an emergency. She repeatedly emphasized Ken's headache to the nurses, since he'd had never had one before, but no one seemed to pay any attention. Much to her chagrin, she learned that, unlike in other Asian hospitals, she would not be able to stay with Ken. Married for over thirty years, they'd only spent a few nights apart, and this crisis would make more.

Ken discovered that, although the hospital catered to foreigners, not all the nurses were fluent in English.

Nurse: How are you?

Ken: My headache is very, very, very bad.

Nurse: Headache? Severe?

The doctors were nice, chatty and personable. Ken's temperature stabilized, but the headache showed no sign of abating. Susan flew in from London the next day. Due to bad winter weather in the US, her flight schedule had been changed several times, and when she got to Heathrow, she had mere minutes to make her plane. She sprinted madly through the airport. She made it, but her luggage didn't. There was not another BA flight for three days. As soon as she reached Bodhisukha, she donned a long skirt of Visakha's and an Indian shirt of Ken's (and a pair of Visakha's undies, which threatened to fall at every step). As soon as she was dressed, she and Visakha made a bee-line for Apollo Hospital, even though she was still flying high on jetlag.

As soon as she got to Ken's beside, Susan carried out a thorough and proper emergency room exam (She couldn't believe that this had not already been done!) to see if there were problems associated with any area of the brain. Ken showed no blurred vision, no loss of peripheral vision, no slurred speech, no problems with balance or coordination, and no confusion. In short, he did fine, so we felt relieved about that. Nevertheless, when, at last, the chief doctor came in, Susan demanded, in a very polite, friendly, and professional way, a CAT scan. To our amazement, the doctor instantly ordered it done, and Ken was whisked away. She also requested a spinal tap (lumbar puncture), but, for some reason, the doctor was reluctant about that. When the CAT scan revealed an "asymmetry," the doctor immediately ordered an MRI. Shortly after Ken returned from this, the doctor announced, "Your sinuses are blocked!" and he prescribed a little extra paracetamol (Tylenol). Susan suggested an injection for pain, and, again, the doctor agreed. Within minutes, Ken watched his headache subside. He was almost his old self (at least, temporarily) when Mrs. Jayawardana and her son Jayadeva of MahaBodhi Book Agency came to visit. They were concerned about Ken and helped a lot. Actually, with his own hospital experience, Jayadeva was extremely skillful at communicating with the nursing staff. For example, he knew they were called "sisters," rather than "nurses."

Once Susan was assured that Ken was out of mortal danger, she, Visakha, and Rajiv headed back to the market in Barasat to shop for some clothes. Underwear, of course, was top priority. Visakha cheered her with a family legend about dear Aunt Dorothy. When the elastic on her panties snapped, just as the city bus pulled up, Aunt Dort simply stepped out of them and boarded the bus as if the panties on the sidewalk had nothing to do with her! Susan was also able to find some salwar suits. Strangely, although they were "ready-made," the sleeves were in a separate package, unattached, so she had to wait for them to be sewn on. Ironically, the salwar pants had neither elastic nor string. After she got back to Bodhisukha, she asked one of the boys and was given miles of hemp twine, a length of which she was able to work through the waistband to keep them up.

|

|

||

|

|||

Beverly arrived from Bangkok the day before the pilgrimage was due to begin. Obviously, Ken was not ready to get on a train, and Visakha would not go without him. Some urgent business had come up for Ven. Nandobatha, so he also could not leave immediately. It was quickly decided that Ven. Kittima and Rajiv would accompany the two women to Gaya; the rest of us would join later if we could. Before they left, Susan spoke with the doctor, who agreed to release Ken into her care. We left the hospital with antihistamine, nasal spray, and lots of pain meds, including the powerful pain medicine he'd gotten a shot of, but this time in pill form, just in case.

With the medication, which Susan had prescribed in substantial doses, Ken's headache receded enough for him to pack to join the pilgrimage. At last, Susan's luggage was delivered to us at Bodhisukha, so we were good to go.

Incredible India: on our way to the train station, we passed a tricycle cart (called "van") loaded with a huge dead buffalo, legs tied together, roped on the flatbed. The two men who were pushing the bike through the streets were untouchable "scavengers" who would recycle the dead buffalo for leather and, perhaps, steaks. Though we were leaving from a smaller station, called Sealdah, we began talking about Howrah Station, which we had experienced many times and which, we had heard, had mightily amazed Susan and Beverly. Elsewhere you don't find people sleeping on the platforms and in every nook and cranny of an old train station. Indeed whole generations are born, live, beg, and die in Howrah. Ven. Nandobatha related the observation of an old Burmese friend: "When I see Howrah Station, I cannot help but doubt the Buddha's teaching that it is "rare to be born a human being!"

|

|

|

We arrived in Buddhagaya about midnight, crashed in the Sujata Hotel, and met Susan and Beverly the next morning at breakfast. Susan immediately suggested that Ken try an antibiotic to tackle the probable sinus infection. In short, it worked. The headache disappeared and the pilgrimage was wonderful.

Winters in Buddhagaya are always filled with Tibetan pilgrims because they welcome the cold, but everywhere we went we encountered other pilgrims from far-flung Buddhist lands: Korea, Japan, China, Thailand, Burma, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, and surprisingly many from Cambodia, in addition to a sprinkling of westerners. All the pilgrims were practicing earnestly, according to their traditions and, like us, were deeply moved and reverent to be where Buddha had walked.

At every holy place, we lit incense and candles, our monk-teachers chanted, and we meditated. Following Bruce's example from that earlier pilgrimage, Visakha printed up suttas, Jatakas, and gathas relevant to each site. Sometimes we read them aloud at the site, sometimes we circulated them and read them privately. We hope to compile some of them into "A Pilgrim's Companion," which will not be a guidebook, but a useful book which will add depth to a pilgrimage such as ours.

Lodging

Four years ago, we stayed in hotels, which were not expensive. Since then they have become prohibitively so, and this time we opted for temples which proved quite comfortable. The Korean temple in Lumbini was particularly nice. The rooms were spacious, and the Korean bedding authentic. Just as in Korea, we slept on the floor, but unlike Korea, the raised floor was concrete without traditional "ondol," or heating ducts. The buffet breakfast (and dinner for those who partook) was plentiful, delicious, and probably as close as possible in the Sub-continent to Korean temple food. The delightful touch was that the doors had no locks, but we still felt perfectly safe.

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

The Burmese temple in Savatthi was perhaps the friendliest place of all. The temple was new, and the layout, with the rooms around a spacious courtyard, attractive. Each room had two bathrooms--one Western and one Asian; very accommodating! Next to the bathrooms, there was a storeroom for pilgrims to leave excess baggage while they traveled elsewhere.

|

|

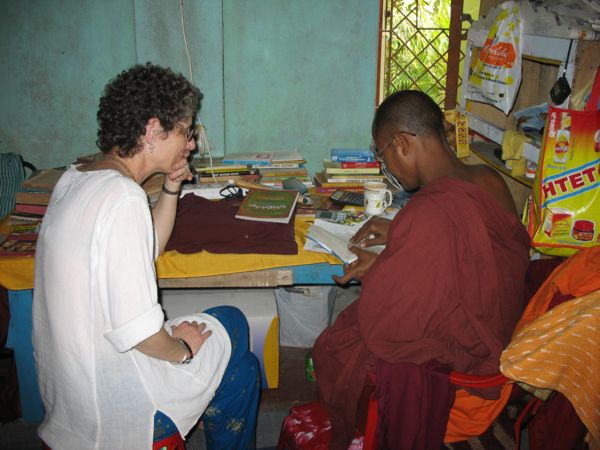

Nalanda

Ven. Nandobatha was able to stay with us for only a few days, but the highlight of his time with us was the ceremony he arranged in Nalanda. Many of our students from the intensive course were also recipients of the Mark Decker Scholarship, so they gathered at the Burmese Monastery there. We were able to offer lunch to all the monks. Then we personally awarded each one his scholarship and listened to several encouraging speeches emphasizing the importance of good English for modern Buddhist monks. That afternoon, the monks guided us around the ruins of Nalanda University and through the museum. We concluded the tour with a visit to the hostel at the Nalanda Mahavihara Institute, where many of them are studying.

|

Patna

|

|||||

|

|

||||

| Click either image to see more photos of Patna | |||||

|

Vesali

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Click either image to see more photos of Vesali

|

|||||||

Kesariya

Our itinerary this year included two places which we had never before visited, Kesariya and Lauriya Nandangarh. On the map, they appeared to be almost directly on the way between Vesali and Kushinara. We had learned from one of the guidebooks that there was an "acceptable" hotel in a nearby town. Ven. Nandobatha advised against the hotel in question and said we had better return to Patna from Vesali. We did and headed the next day for Kesariya. Our plan was to do both sites in one day, but the road to Kesariya was a pot-holed dirt path, and it took us many hours to reach there. Kesariya has been identified with Kesaputta, the town where Buddha gave the Kalama Sutta, his discourse on free and critical thinking. Recent excavations had exposed a huge stupa, reminiscent of Java's Borabudur, but without the carving. It was said to be the largest stupa ever erected, though it did not appear so enormous now. So far, only one side had been excavated, and the base was probably still buried. It was, nonetheless, impressive. The curves and the angles were very graceful. On the upper levels, there were many niches containing images of the Buddha, but they were all broken–none had heads, and some were no more than legs in meditation posture. Along the bottom were rows of cells which had been used as residences for monks. The stupa stood in the middle of rice fields, and, in spite of the difficulty getting there, it seemed popular with local Indian tourists. The monument was swarming with people the whole time we were there and the better roads were closed because of a politician's visit.

By the time we left Kesariya, dusk was approaching, so we decided to stop somewhere before continuing on to Lauriya Nandangarh. The town of Bettiah seemed a good choice, and, fortunately, there was a fairly decent hotel.

Lauriya Nandangarh

The road to Lauriya Nandangarh was perhaps worse (and slower) than the road to Kesariya. On the way, we noted the paucity of birds and trees. Everything looked tired and over-cultivated. There was nothing natural or wild to be seen. All trees, except the revered Bodhi and Banyan, were terribly hacked and lopped off, as if the goal were to see how much could be cut before the poor tree withered away. It was rather like Nasreddin's ass, who learned to eat less and less until he died of starvation.

|

|

||||

|

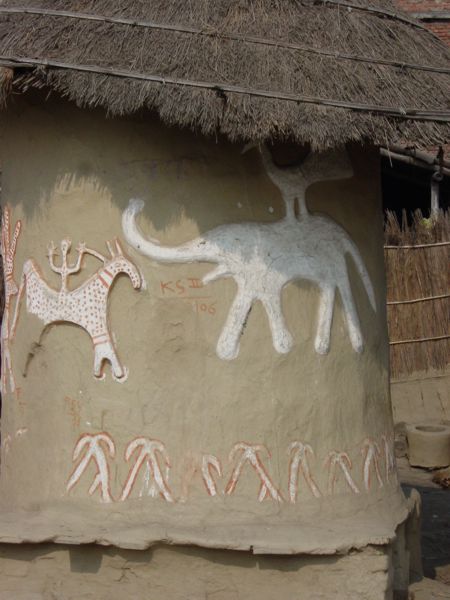

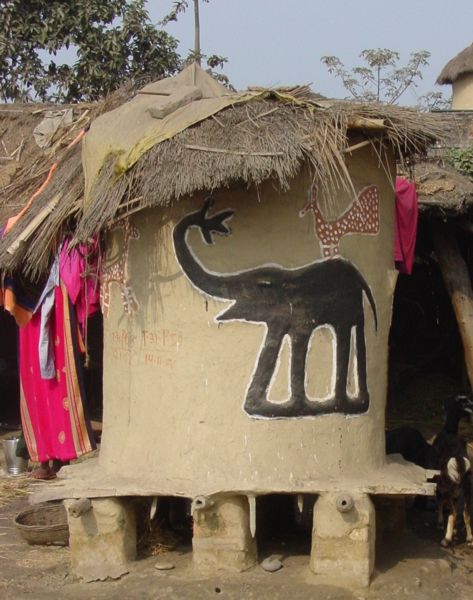

Silos in a village near Lauriya Nandnagarh

|

|||||

The driver had to ask repeatedly for directions, but at last we reached the Ashokan column, the only one, of the many the great king erected, still standing intact in its original location. Even after enduring all those centuries of weather, the polish still shone, and the four inscriptions were as clear as the day they were incised. The lion capital, though the face was damaged when it had been used for cannon practice, was impressive.

Near the column there were several stupas, which, not yet excavated, appeared simply as hillocks. The area was covered with empty plastic bags and other debris from a recent Hindu gathering. Ven. Pannasila told us that the local residents had no idea who Ashoka was, since Indian textbooks referred to him as a "Hindu king." There was no sign or notice board anywhere to teach the people about their own history. Apparently the capital was worshiped as a "lion god."

A few kilometers from the column was a massive stupa, one of the largest in India, with a circumference of 457 meters. It stood in an isolated location, surrounded by trees. Ven. Pannasila had visited the site in 1994 and had found it quite ugly, so he was pleased to see the improvements made by the recent excavation and restoration. The shape of the stupa, with its levels and angles, was similar to Kesariya, but here there was a paved path all the way around the base. When we arrived, there was nobody there at all, so we were able to enjoy quiet circumambulation, vandana, and meditation. Ven. Kittima and Rajiv performed their puja by climbing to the top and meditating on the grassy summit.

The jungle

The route from Lauriya Nandangarh was no better than it had been getting there. Roads were tortuous, and we had to stop frequently to ask directions. Even then we made the odd mistake. We were heading for UP and Kushinagar by a "back road." At one point, very close to the Nepal border, we entered a "tiger sanctuary," with huge hardwood trees, great ferns, bamboo, and rattan creepers. We kept watch for tigers, but all we saw were wild monkeys, both langurs and macaques, by the roadside. About twenty minutes into the jungle, Rajiv asked for a stop so he could answer the call of nature. (Earlier, he had broken our cardinal rule of going whenever we stopped at a toilet). We were still watching for tigers when a car, decorated for a wedding, coming from the opposite direction, stopped beside us. The driver berated our driver at great length. When our driver told him where we were going, the other informed us that we were going the wrong way and that we had missed our turnoff some miles back. As soon as Rajiv was back on board, we turned around and followed the wedding car. After a while, the other car stopped, and the driver got out. He again scolded our driver, explaining that the road was very dangerous--there had been kidnaping and holdups in that area--and directing us to the right road. A few kilometers further, we found a working elephant amid huge stockpiles of teak logs in a forestry department area surrounded by barbed wire. The turnoff led us quickly out of the jungle. On the way to the UP border, we passed many carts loaded with sugar cane. At one sugar mill, we chuckled over the dozen or so monkeys stealing sugar cane as fast as they could.

Hinduism

During our three weeks of travel, we had many experiences with Hindus. We had been asked to meet the official in charge of the book store near the entrance to the Mahabodhi Temple to arrange for several BPS book to be stocked, but he was not in. We happened to encounter him later in the reception hall, and he suggested we meet him in his office. We went to the office at the agreed time, but he was out again. Obviously he didn't care what books were available to pilgrims and he didn't care whether he met with us or not. Of course, the Mahabodhi Temple Management Committee remains Hindu dominated. We heard that, during restoration, workers repairing a wall had desecrated the temple with Shiva linga, tridents, and other offensive Hindu symbols between the ancient lion images. After a barrage of protests, some of these improper additions were removed, but the issue has not been completely resolved.

From Kushinara, our route to Lumbini went through Goraklpur, but the night before leaving, we heard that an influential Hindu mahant, having been denied permission for a rally, had gone ahead with his program, and had been arrested. His followers were demonstrating violently to call for his release. There were riots in the streets, buses burned, and several trains torched. We were advised to avoid Gorakpur. It seemed obvious that the mahant had intentionally provoked the situation to stir up trouble (and rally Hindu voters) just before the Muslim holiday of Ashura. We spent an hour considering options. At last our driver found an alternate route to Lumbini, and we left early the next morning. The alternate route, we learned, was mainly dirt roads over which we proceeded at the fast clip of about 10 kph.

All this political posturing led to a crisis in Uttar Pradesh. When we returned to India, on our way to Savatthi, we encountered a demonstration in Balrampur, which completely blocked an important intersection. Traffic, huge lorries mainly, was held up by lines of men sitting down right in the middle of the crossroad. A matted-haired sadhu dressed in bright orange and brandishing a trident, led them in shouting some chants. We didn't get out, or even open the windows completely, but we could hear lots of hollering, including "Sita Ram, Ram Ram Hari Hari!" Ven. Pannasila translated some of their other shouts, "Glorious Hindustan," "Free our Mahant!" and "We will not allow any insult to our Sadhus in Hindustan!"

|

|

|

Ken surreptitiously took photos through the half-open window. A few Muslim women and children quickly slipped past, looking intimidated. At last, our driver took advantage of an opening between two lorries, and drove through. He drove down some back roads which led in the right direction, through a village of daub and wattle houses. At one point, we were faced with four ox carts in a row! We pulled over, and they squeezed past. In the process, we certainly freaked out a buffalo tethered in front of a house. That pathway probably hadn't seen that much traffic in years. Eventually, the track led back to the main road and we escaped safely from Balrampur

One day, as we crossed the Ganges, we saw Hindu devotees camped on the banks below. They had gathered for a month-long mela, taking daily holy dips in the river, drinking, smoking pot, and washing away all sins.

|

|

Susan had seen some naked sadhus, covered with ash, sitting on the ghats in Varanasi. When we passed several orange-clad sadhus sitting on the crowded sidewalks of Kolkata, she was prompted to ask Ven. Pannasila what these various sadhus were all about.

|

|

He answered, "In Pali, the word 'sadhu' means 'well done' and is reserved for holy, auspicious occasions. When Shankacharya was trying to destroy Buddhism, he gave the word 'sadhu' a military meaning and applied it to the Hindu 'warriors' who publically practice yoga and perform various miracles. Now there are many kinds of Sadhus in India. Some sadhus observe severe austerities, such as sleeping on thorny bushes or keeping their arms over their heads until the muscles atrophy. Some perform physical feats, such as pulling a juggernaut with beard or penis. Many use drugs and alcohol as part of their practice. Some serve the fundamentalist Hindu political party as spies and agitators; some actively fight to promote the Hindutva cause. Some, being idle themselves, attract lazy and mentally-handicapped followers. Some accept offerings of the faithful and live simply. There is no established sila or code of conduct. A few sadhus are very powerful politically and run various Hindu institutions. Among them, there are four Grand Masters, who are seen as chief representatives of Hinduism."

Ven Pannasila described one aspect of Hinduism as "Chamaskar (miracle), Namaskar (respect); No Chamaskar, No Namaskar." This is apparent in cults, such as Sai Baba, where devotees are awed by the seeming magic of the guru producing baubles, watches, etc. from thin air.

Ven. Pannasila told us that in Hinduism here are thirty-three crores of gods and goddesses, and it seems that there are at least that many festivals. We have written about the Durga Festival in Nagpur and Holi in Kolkata. This time we repeatedly encountered celebrations of the Sarasavati Festival. Sometimes it seemed that the noise and loud music were actually following us. Everywhere people had erected images of the goddess on make-shift altars. In some towns we saw many rows of images for sale. (Considering that even a small image cost two thousand rupees, it was quite a profitable business!) To become a good student, there was no need to study: just erect a shrine to this goddess of wisdom, collect donations, play loud music, dance, get drunk, and carouse. At the end of the festival, a Brahman would chant a mantra and collect his fee; the statue would be ignominiously dumped in the river. What wisdom could there be in such a waste of money?

Lumbini

We'd been to Lumbini three times, and, each time, we found it less impressive, less inspiring. Granted, the first time, it was still occupied by villagers. (We remembered the geese chasing Ken as he donated food to Ven. Wimalandanda, who passed away just a few months ago.) There had been a Hindu brahman there, and Ven. Wimalananda. had remarked to us that, although the poor Muslims presented no problem whatsoever, the Hindus were very hostile to Buddhism and Buddhist monks.

|

|

|

|||

|

1983

|

2001

|

2007

|

|||

In 1983, the old Mahamayadevi Temple, with the two bas reliefs, stood beside the Ashokan pillar. The sacred area, including the tank and the Bodhi tree, was rather small, being surrounded by the village, and a Hindu sadhu was collecting money inside the Temple. Still, you could sense the serenity in the place. In 2001, the temple had been destroyed, and a tin roof covered the excavations. The carvings were on display in a temporary structure, where Ken saw a cleaning woman wiping the floor with a Buddhist flag. This time, we found that a new structure, one of the ugliest imaginable, had been built over the excavations. This building, dedicated by the new (and now powerless) Nepalese king, was painted bright red and seemed to us to be devoid of architectural style. Inside, gray steel girders crisscrossed the still mysterious excavations under a low ceiling, creating a very claustrophobic experience. A raised walkway led around the building and to the center, where one could gaze downward at a stone encased in translucent glass and labeled, "This stone marks the exact spot where the Buddha was born." From that spot, one could also gaze upward to get a very distorted view of the ancient bas relief of the birth (and a stiff neck!). Ken noticed that there were two small closed doors at the level of the carving, so he risked the wrath of the guards (Actually, guards neither noticed nor tried to stop him.) and climbed over the barriers on the stairs leading to the roof. Unfortunately, the doors were padlocked, and the small panes were of opaque glass. Indeed, there was nothing Buddhist about the place, and that seemed intentional.

After meditation in the garden we walked to the original Nepalese Buddhist temple. The monk in charge spoke good English, and we talked a bit about conditions. The newer bas-relief from the old Mahamayadevi temple had been cleaned and enshrined in the temple, where it appeared more lovely than ever. The old doors and windows of the temple were carved black wood, a speciality of Newari artists in Kathmandu. On the altar were several images as well as a golden one in Nepalese style. There were also a marble statue of Ven. U Candramani and a framed photo of U Thant. One of the walls was covered by a gigantic painting of the Wheel of Existence. The Lumbini Development Committee had expressed its intention to tear down the Nepalese temple, but the abbot assured us that that would not be possible because that temple was the oldest temple in Lumbini and much older than the Lumbini Project itself.

We had remembered Lumbini as being very cold, so we were surprised and pleased at the mild weather. At night, foxes and jackals sang all around the Korean temple, and a sign posted on the wall warned pilgrims against wandering around.

|

Piprahwa, the site of Kapilavatthu

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|||||

As we headed towards Savatthi, the road felt endless. Suddenly, Ven. Kittima gave a loud exclamation. The car stopped, and we watched a flock of vultures cleaning a bloody carcass with ribs exposed. The vultures had already gorged themselves, but they continued to chase away the crows and a lone dog wanting a share. The huge birds, which we had never seen on the ground except on Discovery Channel, were an amazing sight with their wings spread and necks extended. Our ornithological experience was enhanced by the sighting of several small flocks of storks and peacocks beside the road. We also passed the scene of a traffic accident--in the middle of the road lay a man, with his head smashed, apparently by a speeding truck.

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|||||

Sarnath

On previous trips to Sarnath, fog and scaffolding had prevented us from appreciating the splendor of the great Dhamek Stupa, marking the spot where Buddha taught his second sermon, the Anattalakkhana Sutta. The stupa, with its delicate stucco carving, is magnificent. We were thrilled to circumambulate and to view it from all sides without distraction. The experience was heightened by the presence of many other pious pilgrims, from Tibet, Cambodia, Thailand, and Japan. A group from Sri Lanka was intently listening to a nun as she explained the history and the significance of the structures around the Deer Park. A few hours later, the group had moved to a new location, but the nun was still teaching. Obviously, her lectures were not only guidebook descriptions, but included large doses of the Dhamma.

At the Museum, we were informed that permission to photograph the exhibits had to be obtained in New Delhi. Cameras had to be left in lockers near the ticket office. When we reached the museum entrance, Ken was told that he also had to check the cell phone hanging around his neck. We realized that most phones today (but not ours) can take pictures, record music, and do a thousand other things, which have become part of instant communication. Nevertheless, it was a joy to see the stunning Ashokan lion capital, which is the national symbol of India and the exquisite Dhammacakka image of the Buddha. (Twenty years ago, on our first visit to Sarnath, we had been able to photograph both of these.) The Dhammacakka, which originally stood atop the lions has been broken off, and the fragments were displayed on the wall. Commonly, the Wheel of the Law has eight spokes and, sometimes sixteen. There is a bit of a controversy as to why this early representation has thirty-two. Could it be the thirty-two marks of Mahapurisa, a Great Man? More probably, it represents the twelve stages of Paticca Samuppada, Dependent Origination, forwards and backwards, plus the Noble Eightfold Path.

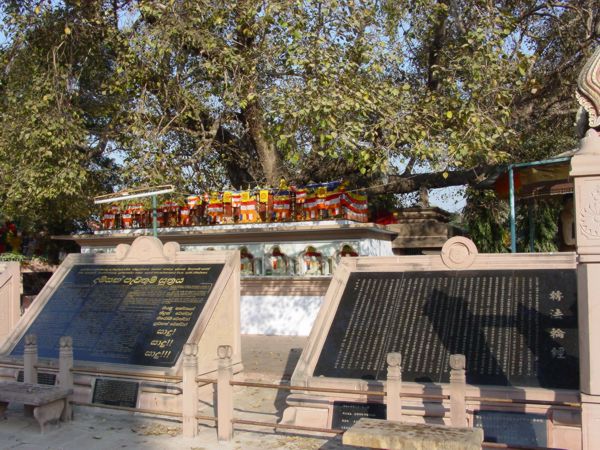

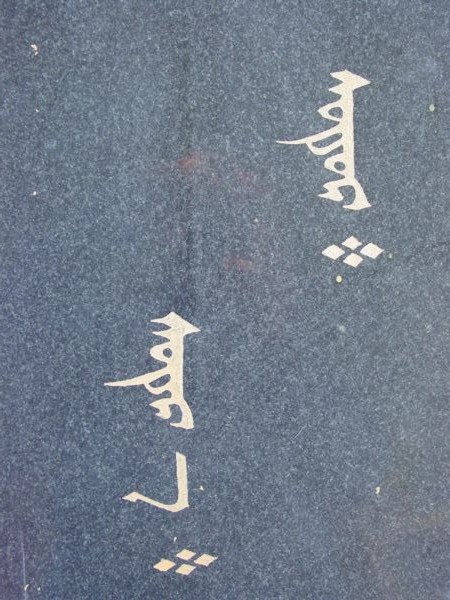

Beside the Sri Lankan vihara, whose walls are adorned with poignant paintings of the life of the Buddha by a Japanese artist, stands a sacred Bodhi tree. Under the tree, the Burmese have placed images of the Pancavaggi listening to the Buddha's first sermon. All around the tree are black marble slabs , on which this Dhammacakka Sutta is inscribed in gold in Pali, English, Burmese, Sinhala, Thai, Chinese, Mongolian, Tibetan, Korean, and several other languages.

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Sri Lankan Vihara

|

The Pancavaggi

|

The Bodhi Tree and the Dhammacakka Sutta

|

Mongolian script

|

||||

The saddest site in Sarnath is just behind the Sri Lankan vihara. The enclosed area includes a small zoo, for which one must pay two rupees to enter. But even that, given the site used to a deer park, where the animals, protected by the king, roamed freely, is not the problem. Inside the zoo, and inaccessible except through the gate, stands the cremation stupa of Angarika Dharmapala, the founder of the MahaBodhi Society. This monument to the man who spent most of his life for the return the Mahabodhi Temple to Buddhist control and for the revival of Buddhism not only in India but in his native Sri Lanka, languishes isolated, fenced in, locked, and totally neglected. Even sadder is the fact that the MahaBodhi Society of India has completely rejected the Buddhist vision of its founder. It is now entirely dominated by Hindu brahmins who cannot see beyond their personal material greed. Visakha registered her complaint to the monk inside the vihara, but, as he sat by the altar collecting donations, it was obvious that his invitation to discuss the matter was not seriously intended.

The saddest site in Sarnath is just behind the Sri Lankan vihara. The enclosed area includes a small zoo, for which one must pay two rupees to enter. But even that, given the site used to a deer park, where the animals, protected by the king, roamed freely, is not the problem. Inside the zoo, and inaccessible except through the gate, stands the cremation stupa of Angarika Dharmapala, the founder of the MahaBodhi Society. This monument to the man who spent most of his life for the return the Mahabodhi Temple to Buddhist control and for the revival of Buddhism not only in India but in his native Sri Lanka, languishes isolated, fenced in, locked, and totally neglected. Even sadder is the fact that the MahaBodhi Society of India has completely rejected the Buddhist vision of its founder. It is now entirely dominated by Hindu brahmins who cannot see beyond their personal material greed. Visakha registered her complaint to the monk inside the vihara, but, as he sat by the altar collecting donations, it was obvious that his invitation to discuss the matter was not seriously intended.

Shopping

At every site on the pilgrimage, one is urged ("Hounded" may be a better word.) To buy guidebooks, maps, images, and a thousand other articles at stalls and by hawkers who accost every pilgrim as he or she alights from a vehicle. Prices vary according to the whim of the seller and the appearance of the potential buyer. In the shop at the entrance to the temple in Kushinagar we purchased small replicas of the Sarnath image for one-tenth of the prices asked by hawkers. In the bookshop of the Sri Lankan temple in Sarnath, Ken bought a wooden replica of the Lion Capital and several sets of postcards, again at a fraction of the street price. We also found many books we wanted, but we simply noted the title, author and ISBN number, and ordered them from MahaBodhi Book Agency, so wouldn't have to carry the extra weight.

Knowing that Varanasi silk is the most famous in India, we asked our driver to take us to a good shop. We were overwhelmed by the beautiful scarves, shawls, and saris. We bought as much as our suitcases could hold. The prices were, we thought, reasonable, but we wondered how much less the salesman would have asked if our skins were brown. Actually, Ven Pannasila related that even Indians cannot always trust local merchants. He related a case where pilgrims from Maharashtra had visited a shop in Varanasi and chosen and paid for goods to be sent to them in Mumbai. What they received, however, were cheap imitations of what they had paid for. Many Indians seem to care only for their own immediate families. This has been a problem in India since ancient times. In the Middle Ages Muhammed al Gazni sent spies to an unconquered area, and the soldiers let their horses graze in private pastures. When a farmer saw them, rather than objecting, he simply moved the horses to another man's field. After this happened repeatedly, al Gazni realized that, since no one cared what befell his neighbor, the country could be easily taken. Ven. Pannasila also told us that his assistants in Buddhagaya often complained when he helped another family's children: "Why are you helping them? You should give that to us!" was a frequent refrain.

|

|

|

||||

|

|

Varanasi

Above: the Ghats Left: Offering lunch at Clarks Hotel |

||||

During the pilgrimage we came to appreciate deeply the privilege of traveling with the monks who taught us so much and to value the noble friendship engendered by the beauties and the hardships we'd shared along the way.

|

||||

|

||||

|

Back in Kolkata

Above: Susan with Vens. Nandobatha and Ariyawantha at Bodhisukha

Click the image at the left for more photos of our excursion into the city. |

|||

Note: All the photos and the description of our pilgrimage in 2001-2002 are still available at <http://www.brelief.org/rn2002/pilgrimage/pli.html>.