Buddhism in India

|

|

| Poverty is not news in India. The crush of people, the crush of destitute people, is numbing. Nearly 260 million of India's more than 1 billion people live below the poverty line. India is the world's largest democracy, but more than half a century after independence from British colonial rule, its entrenched caste system aggravates persistent economic troubles and makes a travesty of the ideals of justice and equality. "Discrimination suffered by women, the lower castes, and tribal groups is a crying denial of the democracy that is enshrined in our constitution," President K. R. Narayanan said recently. What are the origins of the caste system? Nearly a thousand years before Buddha’s birth, nomads speaking an early form of Sanskrit entered the Indian subcontinent from the north-west, probably through what is now Afghanistan, slowly spreading down through the Punjab into north-central India. They settled into villages and merged with the local population In this caste-bound society, there were some homeless dropouts called samanas who played little or no part in the economy as either producers or consumers. They devoted themselves to the search for religious truth, but they did not follow the prevailing religious orthodoxy, the Brahminical religion based on the Vedas. They were highly individualistic and engaged in a variety of practices. Most samanas were celibate wanderers, without families or other social ties. They could travel freely even from kingdom to kingdom. Being respected by all levels of society, they were given food and hospitality. Some were teachers, arguing their philosophies of materialism, nihilism, determinism, and eternalism. Listening to such debates was actually a popular form of entertainment. Many samanas sought to develop psychic powers. Some were naked and unbathed, others wore loin clothes and bathed three times daily. Some followed bizarre rules and practices. |

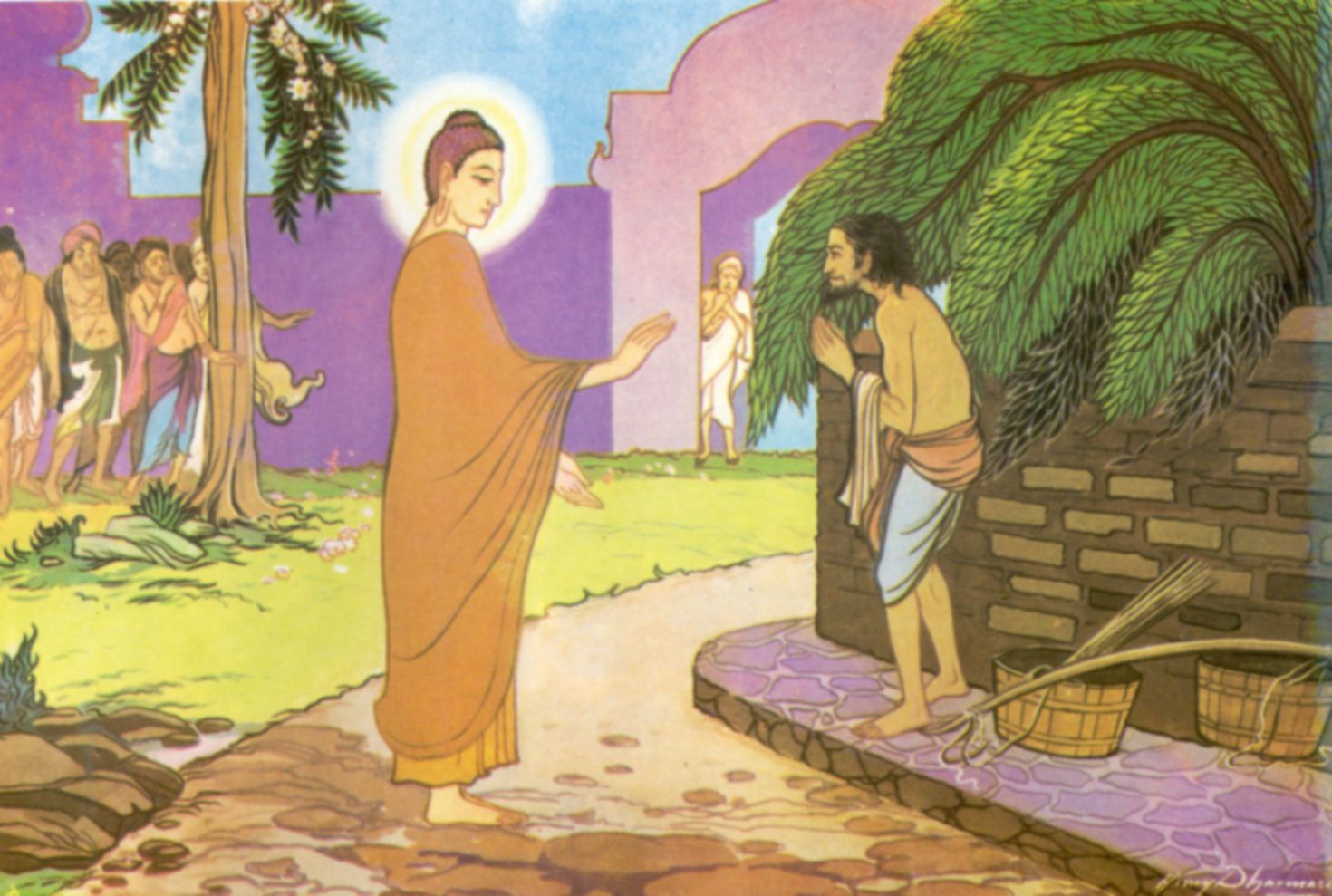

Buddha accepting a request for ordination from the Untouchable, Sunita. (From Buddhism in Pictures, The Buddhist Information Center, Sri Lanka) |

|

From these forest wanderers came new strains of mysticism as well as the organized religions of Buddhism and Jainism. The culture wars of the first millennium B.C. set the Brahminical tradition against the samanic one. The samanic faiths were almost as pluralistic as today, but what they had in common was their refusal to accept the authority of the Vedas and the Brahmins. |

| Buddha denied all authority to the Brahmins and their scriptures. Brahminical rites--indeed, all rites and rituals--were useless and pointless. Buddha condemned animal sacrifices, preaching the doctrine of ahimsa, non-violence, which, because of it association with Mahatma Gandhi, has often been mistaken for a Hindu principle. Buddha refuted the idea of an omnipotent creator-god by demonstrating that the universe develops according to laws of causation. He denied the existence of a cosmic soul, further demonstrating that man has neither soul nor enduring self. Buddha never used Sanskrit, the language of the Brahmins, but taught in the vernacular Magadhi, which was later arranged into Pali. The Sangha was open to all, both men and women, regardless of caste. Although members of the untouchable castes were often forbidden entry into Brahmin temples, Buddhist monks taught them freely and ordained those who wished to enter the Sangha, where members were ranked only by seniority. In a number of Jatakas, Buddha described previous births when he had been born as a candala. |

An Untouchable and his wife. |

| Those who naively believe that the caste system is a class system are wrong. Class differential can be found all over the world, but the caste system exists only in India, where it is an inseparable part of Hinduism, upheld by the holy books. The Laws of Manu and the Bhagavad Gita are the root causes of the oppression of untouchables. Sir Winston Church declared, "These Brahmins who mouth and patter the principles of Western Liberalism, and pose as philosophic and democratic politicians, are the same Brahmins who deny the primary rights of existence of nearly sixty million of their fellow countrymen whom they call 'Untouchable' and whom they have by thousands of years of oppression actually taught to accept this sad position. They will not eat with these sixty millions, nor drink with them, nor treat them as human beings. They consider themselves contaminated even by their approach. And then in a moment they turn round and begin chopping logic with John Stuart Mill or pleading the rights of man with Jean Jacques Rousseau." Today, there are approximately 160 million Untouchables, more than one-sixth of India's population, at the bottom of India's caste system. They are discriminated against, denied access to land, forced to work in degrading conditions, and routinely abused by police and by higher-caste groups that enjoy the state's protection. In what has been called India's "hidden apartheid," entire villages in many Indian states remain completely segregated by caste. National legislation and constitutional protections only mask the social realities of discrimination and violence faced by those living below the "pollution line." |

| When the Untouchable movement began in the 19th century, some militants rejected their identity as Hindus and saw an alternative in Buddhism. Pandit Iyothee Thass, a Tamil, argued that Tamils were originally Buddhists. Brahmananda Reddy organized a small Buddhist movement in Andhra Pradesh. There were also several brilliant upper caste intellectuals, such as Dharmananda Kosambi, who identified themselves with Buddhism. During the struggle for Indian Independence, two leaders claimed to be the champion of the Untouchables. Mahatma Gandhi called them Harijan, a preposterous euphemism which means "Children of God." Gandhi espoused the need for guaranteeing certain rights to the Untouchables, but he was himself a Brahmin. Gandhi believed the caste system to be a healthy institution and strongly defended it: "How can a Muslim remain one if he rejects the Koran or a Christian remain a Christian if he rejects the Bible? If Caste is an integral part of the holy books of Hindus which define Hinduism, I do not know how a person who rejects Caste can call himself a Hindu?" Aware of statements like this, Untouchables hardly consider Gandhi a hero. Diametrically opposed to this viewpoint was that of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, who was born in 1891 into the untouchable Mahar caste of Maharashtra. At a time when less than 1 percent of his caste was literate, Dr. Ambedkar obtained a Ph.D. from Columbia University in New York and a D.Sc. from the University of London. He coined the term Dalit or "broken people" which is now in common parlance. His earliest efforts involved establishing a Dalit movement in Maharashtra by founding newspapers, holding conferences, forming political parties, and opening colleges to promote the education and welfare of Dalits. In the 1930s, as a delegate at the London Roundtable Conferences, he argued that Dalits were a minority entitled to their own electorate. He also led campaigns for religious rights for Dalits, including lifting prohibitions on allowing Dalits to enter Hindu temples. He was named the minister for law in the first Nehru cabinet in independent India and served as chairman of the drafting committee for the constitution. |

Dr. B. R.Ambedkar |

| Untouchability was abolished under India's constitution in 1950, and certain rights and quotas are reserved for the "scheduled classes," mainly due to the efforts of Dr. Ambedkar. This has not in any way, however, led to the elimination of discrimination of Untouchables. The practice remains very much a part of rural India. Newspaper accounts of attacks on Untouchables are commonplace. Dalits in India are still being burnt alive, their women raped, their children murdered. Dalits dare not cross the line dividing their part of the village from that occupied by higher castes. They cannot use the same wells, visit the same temples, drink from the same cups in tea stalls, or lay claim to land that is legally theirs. Dalit children are frequently made to sit in the back of classrooms. Most Dalits continue to live in extreme poverty, without land or opportunities for better employment or education. Most are still relegated to menial jobs–scavengers, toilet cleaners, removers of dead animals, leather workers, and street sweepers. Many Dalit children are sold into bondage to pay off debts to upper-caste creditors. Tens of millions of Dalit men, women, and children work as agricultural laborers for as little as Rs.15 to Rs.35 (US$0.38 to $0.88) a day. Those who suffer the most are women. Dalit girls have been forced to become prostitutes for upper-caste patrons and village priests. Sexual abuse is used by landlords and the police to inflict political "lessons" and to crush dissent within the community. A government official of Tamil Nadu once pointed out that the raping of Dalit women exposes the hypocrisy of the caste system in that "no one practices untouchability when it comes to sex." Dr. Ambedkar believed that Hinduism itself, because it was so tightly identified with the caste system, was the major cause of oppression. Gandhi, on the other hand, sought to improve the lot of Untouchables within the framework of Hinduism. In debates with Gandhi in the 1930s, Dr. Ambedkar put forth the challenge that if all Hindu scriptures that supported caste were thoroughly renounced, he could continue to call himself a Hindu. If they were left in place, then he could not. He saw the need for a religion that would provide the spiritual and moral basis for equality as an integral part of these struggles. |

| In 1935, Dr. Ambedkar made the bold pronouncement, "I was born a Hindu, and I had no choice about that. But I will not die a Hindu!" This sent a tremor throughout much of India. For the next twenty years, leaders of other major religions, mainly Muslim and Christian, tried to lure him. During this time, Dr. Ambedkar investigated these other religions to discover which offered Dalits the most advantage and protection. By 1956, he had reached his decision. On the full-moon day of October in that year, in a public ceremony in Nagpur, he led 500,000 Dalits in taking precepts and accepting Buddhism as their new faith. The precepts were administered by the Arakanese monk, Ven. U Chandramani. Dr. Ambedkar clearly explained why he preferred Buddhism to all other alternatives. Primarily, he found three principles in Buddhism which no other religion offered. Buddhism teaches wisdom, as against superstition and supernaturalism; love and compassion in relations with others; and complete equality. Considering Marxism, Dr. Ambedkar recognized that the communist movement had shaken the religious systems of many countries, but he did not see that it had provided a solution. Not only failing to eliminate poverty, Marxism, he said, used poverty as an excuse for sacrificing human freedom. Dr. Ambedkar said that Buddhism teaches social freedom, intellectual freedom, economic freedom and political freedom--equality not only between man and man but also between man and woman. |

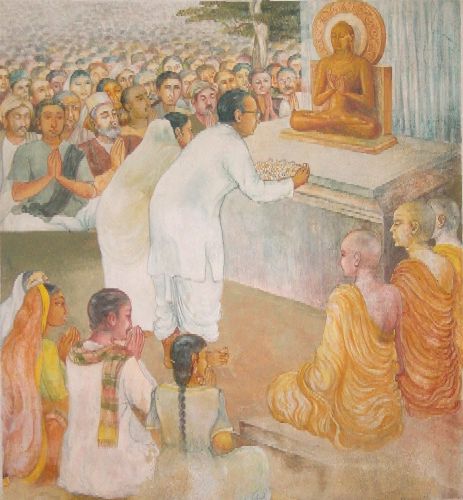

Dr. Ambedkar and his wife taking precepts in Nagpur in 1956. |

|

Dr. Ambedkar felt it was necessary to preserve Buddhism in India and to protect it from corruption by Hinduism. He exhorted his followers to swear not to regard Vishnu, Shiva, Rama, Krishna, or any of the other Hindu deities as gods nor to worship them. He denounced as malicious propaganda the Hindu claim that Buddha was the incarnation of Vishnu. Dr. Ambedkar vowed never to perform any Hindu ceremony or to offer food to Brahmins. He promised never to act against the tenets of Buddhism. Following his example, New Buddhists proclaim their belief in the equality of all people. Since Dr. Ambedkar's renunciation of Hinduism, millions of Dalits have followed suit and taken refuge in Buddhism Most converts have come from Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh. According to the 1990 census there were 6.4 million Buddhists in India. Five million of these were in Maharashtra, the remainder includes traditional Buddhist populations in the hill areas of northeast India (West Bengal, Assam, Sikkim, Mizoram, and Tripura) and high Himalayan valleys (Ladakh District in Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and northern Uttar Pradesh), as well as Tibetan refugees. This was a 35.9 percent increase since 1981, making Buddhism the fifth largest religious group in the country. New Buddhist communities have experienced significant social changes, including a marked decline in alcoholism, a simplification of marriage ceremonies, the abolition of ruinous marriage expenses, a greater emphasis on education, and a heightened sense of identity and self-worth. The conversion of Dalits and the growth of Buddhism in India must be viewed against the backdrop of the recent resurgence of militant Hinduism. Hindus have violently opposed the mass conversion ceremonies. Some Dalits have been beaten as they attempted to travel to Bodhgaya for such ceremonies while others have been turned back by local police. |

|

For the past four years India has been led by a coalition government led by fundamentalist Hindus. Although these Hindu leaders have publicly pledged themselves to preserve Indian's secular tradition and religious diversity, they have at the same time appealed to and championed the rampaging extremists who threaten Muslims, Christians, and Dalits demanding that India formally become a "Hindu nation." They claim that Hinduism was the primeval religion of India. In their skewed view of history, there was no Aryan invasion, no subjection of Dravidians, no society before the establishment of a fixed caste system, no Buddhist kingdoms, no King Asoka. They recognize the magnificence of the great university at Nalanda, but not its Buddhist tradition. They argue that until the Muslim invasions, all Indians were Hindus. The Muslim invaders destroyed Hindu temples and built mosques on the rubble. These foreign terrorists pointed their swords at Hindus and forcibly converted them to the alien faith of Islam. Because of this injustice, patriotic Hindus now have the duty to reverse that history. This, roughly put, is the Hindu nationalist creed. It explains why the construction of a Hindu temple in Ayodhya, a small town in Uttar Pradesh, is so important to them. They claim that Ayodhya is the birth place of Rama, one of the avatars of Vishnu. There is absolutely no evidence that the mythological god Rama was ever "born" anywhere, of course, but the claim seeks to validate Hindu aggression towards India's downtrodden Muslims. |

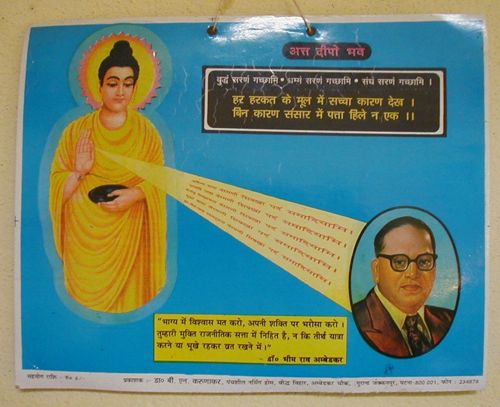

Poster of Buddha and Dr. Ambedkar, displayed in many homes of New Buddhists in India |

| During our pilgrimage, we were fortunate to meet many Indian Buddhists, both monks and laymen. One Brahmin and his family were moved to convert to Buddhism after a notorious incident in which Hindu fundamentalists attacked and killed a Christian missionary and his sons by burning them alive in their camping van. A university professor and his wife invited us for lunch near Nalanda. The Buddhist altar was prominent in their neat home. They were proud to explain that their small village had been the birthplace of Sariputta, one of Buddha's foremost disciples. Even in that village, they had been ostracized by their neighbors when they took refuge in Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha. They expressed pity for the villagers around them, tightly bound by the crippling traditions of Hinduism. We were astonished to learn that there were more than 50 different caste groups in that tight cluster of houses. As we returned along the narrow dirt road, it was obvious which poor huts belonged to the Untouchables, in this case, makers of alcoholic toddy. Another Buddhist in Nalanda showed us his fine collection of ancient artifacts, including Buddha images, shards, and coins which had been turned up during plowing. He explained that the fields in the Middle Land are littered with evidence of Buddhism's glorious past. It is a shame that not a single sacred Buddhist site in India is controlled by Buddhists. Around the beginning of the twentieth century Anagarika Dhammapala founded the MahaBodhi Society, with the goal of gaining possession of the MahaBodhi Temple, but today the temple compound is controlled by a singularly corrupt Hindu-dominated committee. The other Buddhist sites do not fare much better. As the pilgrim tries to worship at the Nibbana Temple in Kushinara, the Bodhi Tree in Savatthi, or any of the other sacred sites, he is incessantly bothered by local officials, including official "caretakers" from the Archaeological Survey of India, for donations, which are quickly pocketed. The prospects for the resurgence of Buddhism in India seem quite hopeful, but there are formidable tasks ahead for the new Buddhists. There are not enough monks to teach the growing Buddhist communities, and the monks already ordained need much more training. The Buddhist countries around the world must help in supporting a bhikkhu training center in India. The best place for this is in the city of Nagpur, which is already a center for Buddhist activity since it was the site of Dr. Ambedkar's conversion. There is also a great shortage of Buddhist books in Hindi and the vernacular languages. India may never again become a Buddhist nation, but all Buddhists hope that someday Buddhism will have a stronger presence and influence there. The country would certainly benefit from the steadying influence of the Dhamma. Buddhists everywhere are indebted to this, the greatest legacy of India. Let us repay our debt by assisting local Indian Buddhist communities and the Indian sangha by supporting them in publishing, education, and politics, so that Buddhism may again flourish and that Buddhists may regain control over the sacred sites. Buddhist Relief Mission would very much like to become a part of this urgent effort. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||